| The most obvious

distinctions between mammals and reptiles are the fact that mammals have

hair or fur, and mammary glands which they use to nourish their young.

These features do not fossilize, and no known mammals have left hair or

fur impressions in the rock surrounding their fossils. Fortunately, however,

there are also a number of skeletal differences between reptiles and mammals.

For one, reptiles have a mouth filled with several teeth which are more

or less uniform in size and shape; they vary slightly in size, but they

all have the same basic cone-shaped form. By contrast, mammals tend to

have teeth which vary greatly in size and shape; everything from flat,

multi-cusped molar teeth to the sharp cone-shaped canines. In reptiles,

the lower jaw is comprised of several different bones, which hinge

on the quadrate bone of the skull and the angular bone of

the jaw. In mammals, however, the lower jaw is comprised of only one bone

- the dentary, which hinges at the quadrate of the skull.

In mammals, there are three bones in the middle ear, the malleus,

incus and stapes (also known as the hammer, anvil and stirrup).

In reptiles, there is only one bone - the stapes. The reptilian

skull is attached to the spine by a single point of contact, the occipital

condyle. In mammals, the occipital condyle is "double-faced". The classic

reptilian skull also has a small hole, or "third eye" through which the

pineal body extends - a trait not found in any known mammal.

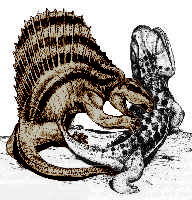

This brings

us to the synapsid reptiles. Like mammals, they have a single, lower temporal

fenestra. Already this makes them more akin to mammals than other reptiles,

albeit with a very reptilian body; legs sprawled out, long whip-like tail,

basically conical-uniformed teeth, etc.. One group of synapsid reptiles

in particular, the therapsids, seem to break these rules and are

adorned with very mammalian characteristics; in the more advanced forms,

many of the bones absent in mammals were already being reduced to near

extinction, and the "third eye" so small it might as well have been absent.

[Romer, 1967, p. 226]

Colbert and

Morales (1991, p. 127) describe the transitional

nature of the tritylodonts in particular:

This transitional series is not as mythical as Gish is trying to purport. Indeed, the transition can clearly be seen in triassic therapsids - though obviously occurring differently than Gish describes! Flank (1995) writes:

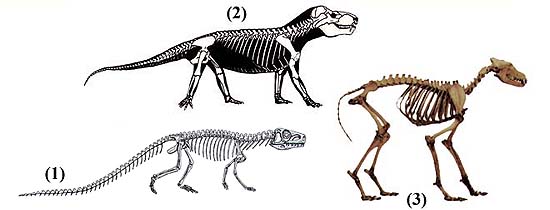

Next

in the reptile-to-mammal transitional sequence are the cynodonts.

Pictured here is Cynognathus, a classic example of the cynodont

reptiles. Of course, when faced with a specimen such as this, one is forced

to wonder if it can truly be called a "reptile". The skull appears basically

mammalian, the hip structure seems basically mammalian as well, but with

very distinct similarities to reptiles as well. Also notice that the grastral

ribs and vertebrae seem to be forming a primitive breast-bone (sternum)

- and strikingly resembles the gastral ribs/vertebrae of the earliest mammals

from several orders. The gastral "floating" ribs have been reduced to almost

nothing, and they are completely absent in mammals, yet very large in reptiles.

This animal isn't quite a mammal, but it isn't quite a reptile either.

This animal truly appears to be ½ reptile and ½ mammal. It

is a perfectly intermediate form. Next

in the reptile-to-mammal transitional sequence are the cynodonts.

Pictured here is Cynognathus, a classic example of the cynodont

reptiles. Of course, when faced with a specimen such as this, one is forced

to wonder if it can truly be called a "reptile". The skull appears basically

mammalian, the hip structure seems basically mammalian as well, but with

very distinct similarities to reptiles as well. Also notice that the grastral

ribs and vertebrae seem to be forming a primitive breast-bone (sternum)

- and strikingly resembles the gastral ribs/vertebrae of the earliest mammals

from several orders. The gastral "floating" ribs have been reduced to almost

nothing, and they are completely absent in mammals, yet very large in reptiles.

This animal isn't quite a mammal, but it isn't quite a reptile either.

This animal truly appears to be ½ reptile and ½ mammal. It

is a perfectly intermediate form.

The proto-mammal Adelobasileus is thought to be either (1) the common ancestor of all mammals, or (2) a very close relative of that common ancestor [Hunt, 1997]. The next proto-mammal (Sinoconodon) appears 208 million years ago. Its cheek-teeth are now permanent, as in modern mammals, however the other teeth are still replaced several times (as in reptiles). The mammalian-joint of the jaw is "stronger, with large dentary condyle fitting into a distinct fossa on the squamosal...[t]his final refinement of the joint automatically makes this animal a true 'mammal'...[r]eptilian jaw joint still present, though tiny." [Hunt, 1997] The rear of the braincase has also expanded and the eye socket is fully mammalian. Hunt (1997)

describes a group of proto-mammals appear roughly 3 million years after

Sinoconodon:

The mammals continued to evolve and several other links are known from the mesozoic era, and "by the late-Cretaceous the three groups of modern mammals were in place: monotremes, marsupials, and placentals." [Hunt 1997] |

|||||||||

| References

Alfred S. Romer, The Vertebrate Story, University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL, 1967 in The Therapsid-Mammal Transitional Series [Online] L. Flank (1995). Available: http://www.geocities.com/CapeCanaveral/Hangar/2437/therapsd.htm [2000, July 10] Duane Gish, Evolution? The Fossils Say No! Creation-Life Publishers, San Diego CA, 1972, re-printed 1978 in The Therapsid-Mammal Transitional Series [Online] L. Flank (1995). Available: http://www.geocities.com/CapeCanaveral/Hangar/2437/therapsd.htm [2000, July 10] Edwin Colbert and Michael Morales, Evolution of the Vertebrates; A History of Backboned Animals Through Time, Wiley-Liss, New York NY, 1991 in The Therapsid-Mammal Transitional Series [Online] L. Flank (1995). Available: http://www.geocities.com/CapeCanaveral/Hangar/2437/therapsd.htm [2000, July 10] S.G. Lucas and Z. Lou, Adelobasileus from the upper Triassic of west Texas: the oldest mammal, J. Vert. Paleont, 1993 in Transitional Vertebrate Fossils FAQ [Online] K. Hunt (1997) Available: http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/faq-transitional.html [2000, July 11] The Therapsid-Mammal Transitional Series [Online] L. Flank (1995). Available: www.geocities.com/CapeCanaveral/Hangar/2437/therapsd.htm [2000, July 10] Transitional Vertebrate Fossils FAQ [Online] K. Hunt (1997) Available: http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/faq-transitional.html [2000, July 11] |